itselectric establishes best practices for curbside EV chargers.

- Millions of drivers around the world live in dense urban neighborhoods where they have no driveways, and thus no possibility of installing a home EV charger. That’s a problem—and the pre-eminent solution is curbside charging.

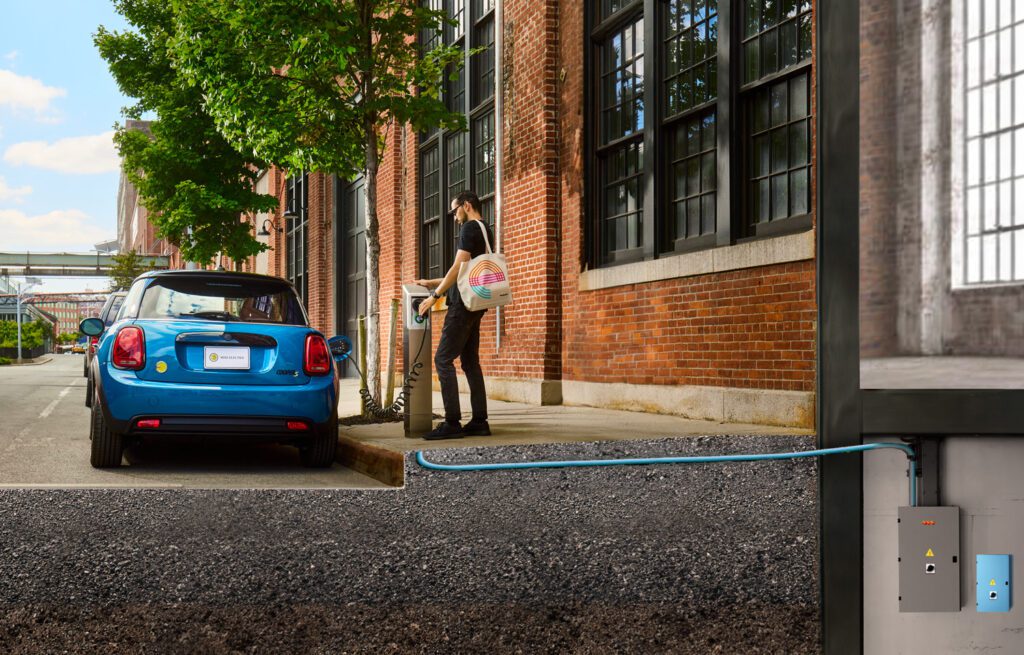

- Curbside charging is not the same as destination charging. To fit into the urban streetscape, a curbside charger needs to be compact, and it doesn’t need an attached cable to create clutter and tripping hazards. That’s why itselectric designed its own charger, with a detachable cable.

- itselectric’s chargers get their power from host properties, behind the meter. This avoids the expense and delays involved in getting a utility interconnection—a major challenge for many public charging projects.

Q&A with itselectric co-founder and CEO Nathan King.

For the last few years, the EV industry has been agonizing over the problem of providing charging for urban drivers who depend on on-street parking, and have no possibility of installing chargers at their homes. EV journalists, including your favorite, have spilled much virtual ink over what once seemed an intractable issue that threatened to hobble the EV transition.

Nowadays however, a visit to some of the world’s most electrified cities makes the solution plain: lots and lots of curbside public chargers. In Europe, Oslo, Amsterdam and London fit this description, as do several Chinese cities. The US is just starting to catch on to the potential of curbside charging, and this presents opportunities for North American operators to learn from what is and isn’t working in Europe.

The field of public EV charging is divided into several categories—curbside charging is not the same as destination charging, workplace charging or highway fast charging. Successfully deploying curbside charging requires creative ways of thinking about the hardware, the business model, and the supply of electrical power, as Nathan King, co-founder and CEO of curbside pioneer itselectric, explained to Charged.

Charged: I’m keen on curbside at the moment, because I just got back from London, where I saw lots of EVs, and lots of curbside chargers. Your company focuses on curbside charging, and you approach things differently from the typical charge point operator. For one thing, you use a behind-the-meter power connection for your chargers.

Nathan King: That’s definitely one of the things we are doing differently. I would say most of the companies that are operating as curbside charging networks are based on a direct-to-utility connection.

Also, in North America, we haven’t really seen a network operator come to the curbside charging space. Where you do see curbside charging in North America, it’s based on an OEM model where the companies are selling the chargers to a utility or to a municipality, which then owns and operates them. What we’re trying to do is to bring the network operator model to the US, but skip some of the permitting difficulty that you encounter when you’re trying to connect directly to a utility main.

Charged: So the ChargePoints and the EVgos of the world aren’t doing curbside charging?

Nathan King: Well, you will occasionally see a ChargePoint charger in the roadway. There’s actually a handful in the District of Columbia. But in that case, DC is procuring the chargers and installing them. New York City also has some chargers on the curbside. Those were made by a Canadian company called Flo, which sold the chargers to the city for them to operate.

“In North America, we haven’t really seen a network operator come to the curbside charging space. The Level 2 charging industry really is based on an OEM model.”

The Level 2 charging industry in North America really is based on an OEM model. Companies like ChargePoint and Blink build the chargers, and try to get them procured by cities. Then the cities or the utilities have to figure out how to own and operate those chargers. We take the logistics of doing the installations and operation away from cities and utilities, and we earn revenue from the chargers ourselves. So, we’re not actually selling chargers, we’re installing and operating them.

This is how it’s being done in the EU and the UK. We’re trying to bring this owner/operator model to the US, and curbside is an area where that model is possible because there’s really high utilization potential. If you put a charger in, for example, a supermarket parking lot, you won’t expect 24/7 use of that charger because people are doing opportunity charging. Maybe they’re plugged in for one or two hours while shopping. For a Level 2 charger, that’s not a ton of power that’s being transferred over those couple of hours.

But when you put a charger on the curbside, that charger can be used by people who live in that neighborhood and park their cars on the street overnight every day. So now you have 24/7 availability to hundreds or thousands of vehicles that park within walking distance of that charger, and you see high utilization.

What is curbside charging, exactly?

Charged: It may be a subtle distinction, but how would you define the difference between curbside charging and plain old public charging?

Nathan King: The other term we sometimes use is right-of-way charging. The distinction is that our chargers in all cases are going to be installed on publicly owned property. Think about somebody’s sidewalk in front of their building. The city owns and manages the rights to that sidewalk and the parking spot that’s next to the sidewalk. However, property owners have certain rights and responsibilities for that frontage. You’ve got to shovel the snow in the winter, and you’ve got to pick up your trash. On the other hand, property owners can take advantage of their sidewalk frontage in various ways. In some cases, commercial properties install their own lighting. Here in the Northeast, people sometimes install electric snow melting systems underneath their sidewalks. Because you have that frontage, you can make improvements to it that are permitted by the city.

So, there’s a bit of a gray area when it comes to property owners’ relationship to their sidewalks, and that lets us take out a permit from the city on behalf of the property owner to install an EV charger. We always have to have permission from the city to operate. But we’re also working with the property owner for them to supply the power.

“Our chargers are installed on publicly owned property. Property owners earn revenue from providing EV charging to their community, but they don’t have to worry about managing the parking spots.”

The other thing that’s interesting about this right-of-way charging model is that the parking space itself is managed by the city. One of the issues that we see in places like apartments, condos, workplace charging, is that the property owner becomes responsible for enforcing EV charging at that spot. For example, if you’re a supermarket and an ICE vehicle parks in front of that charger, do you tow the vehicle? Or do you just let it sit there and annoy your EV driver customers? There are other things as well, like determining pricing structure and overstay fees, that can add operational complexity for a private property owner.

What we’re unlocking is a model where property owners are able to earn a little bit of revenue from providing EV charging to their community, but they don’t have to worry about managing the parking spots, since those parking spots are managed and maintained by the city.

Our chargers are installed on publicly owned property. Property owners earn revenue from providing EV charging to their community, but they don’t have to worry about managing the parking spots.

Charged: You offer a turnkey service. You procure the hardware, do the installation, and handle all the billing and maintenance. Do you do that in-house, or do you contract with other companies?

Nathan King: We’re a fairly lean team in terms of our operations, and a lot of what we do is subcontracted out. Even larger companies like Tesla or Electrify America, they may have some electricians on staff, but by and large, the design and installation work is being done by subcontractors. We’re doing the same thing.

The right charger for the right job

Charged: Tell me about the charging station itself. Does somebody build those for you to your specifications?

Nathan King: That’s right. We saw the need to have a dedicated curbside charging hardware in North America. In the EU, curbside charging is based on a bring-your-own-cable or a detachable cable model. We don’t have that in the US. Generally speaking, when you encounter a charger, it’s going to have a cable attached to it. The untethered cable makes a lot of sense for curbside for a couple of different reasons, and that’s why we invested in our own design. You can’t go and buy an untethered cable that works in the US right now.

Charged: I’m surprised. Is there really not a single company that sells those in the US?

Nathan King: We were surprised too. And right now, we are first and only. I’ll tick through the advantages. The first is that it presents a smaller, cleaner, compact design. We won an RFP in Boston, and part of the reason that we won is because of the design of the charger. Boston has very narrow streets. There’s not a lot of room on the sidewalk. Finding a piece of hardware that fits within the urban landscape and doesn’t take up too much space, that’s a very important consideration.

The detachable cable allows you to do that. Once you add a cable, you then have to figure out how to manage it. What you might see in a parking garage is a little hook where you expect drivers to loop the charger, or a little receptacle for drivers to plug it back in. Sometimes people just mic drop the charger and it gets left on the ground. On curbside installations, you see cable management systems that keep the cable lifted up off the ground. This adds bulk and complexity, and it doesn’t always work.

The other thing is the repair and replacement of the cable. On the West Coast, we see a lot of issues with copper theft. People think that there’s a lot of copper and that it’s easy to get out of these cords. And it’s actually really hard to replace those cables once they’re cut from the charger. You may have to recommission the charger. You can’t just replace the cable. You’ve got to do a series of tests to make sure the cable’s functioning properly. It’s expensive, and there’s also downtime while you’re waiting for the charger to be prepared.

“Everything is shifting to the J3400 standard. We give the driver the cable that fits their charging inlet. Drivers don’t need an adapter, and we don’t need to replace the connectors.”

With our system, the drivers keep their cables with them, so there’s less opportunity for people to vandalize the cable. Then if it does happen, we’re not rolling a truck, we’re not waiting for replacement parts to arrive—we just send that driver another cable.

The third advantage is our flexibility in charging standards. Everything is shifting over to the J3400 (NACS) standard, but we still have around a million cars with the J1772 charging inlet, including cars that are being sold this year. We give the driver the charging cable that fits their charging inlet. Drivers don’t need an adapter, and we don’t need to worry about coming back to these chargers in two or three years and replacing them with an NACS connector. We’re future-proofed on this charging standard.

Charged: What kind of plug is it where your cable plugs into the charger?

Nathan King: The port on the charging post itself is a universal non-proprietary standard—it’s a J3068, the same standard that’s being used in the EU and the UK. We will be interoperable with the existing technology that’s currently functioning in the US, and we expect if anybody else develops a detachable cable charger in North America, then they’ll also use J3068. Just to make it clear, when you get a charging cable from itselectric, it’ll also work with other detachable-cable chargers.

Charged: Who makes the chargers for you?

Nathan King: It’s a company called Gyre9, based in Connecticut. They have their own line of EV chargers that they manufacture and sell. They also do prototyping and product development, so they were really a great partner for us. We didn’t see any charger in the North American market that offered the right design to scale this up, so we designed our own charger. It’s completely Build America/Buy America-compliant.

Who needs utilities?

Charged: Another innovative thing you’re doing is sidestepping some of the hassle of dealing with utilities by doing a submeter thing. Can you really do an end run around the utility like that?

Nathan King: The short answer is: typically, yes. Every utility has different arrangements for how they manage what they call a franchise. A utility has special permission to build underground lines and have them powered. Now, when we go into a new municipality, one of the first things we do as due diligence is to validate our plans with the utilities we’re working with. It’s a dialogue and it’s a process, but generally speaking, wherever we currently have deployment plans, we’ve spoken with the utility and gotten their buy-in for what we’re trying to do.

There are different ways that we’re going to do it. In some cases, we may work with the utility to get a dedicated meter with our own account. We’re just putting a new meter next to the existing meter that goes to the house or the commercial property. We have a lot of homeowners right now that we’re talking to, but we’re also working with commercial properties, multifamily buildings. We’d love to further expand into institutional property owners like schools and universities.

“Even with fairly low utilization, it’s anywhere from $800 to $1,000 a year that the property owner is receiving in passive income.”

So, sometimes we will have a meter that is dedicated for the single charger, or maybe two chargers that we’re attaching to it. And sometimes we’ll just find spare capacity on the existing house panel and tap into that, and we work out a way to reimburse the property owner for the power we pull. As part of our hardware package, we have a revenue-grade submeter, as any publicly accessible Level 2 charger has, that tracks the power that we’re pulling. We always know how much power is going through our charger, and then we can reimburse the property owner for their utility bill.

Sometimes one way has advantages over another, but in all cases, we’re handling the installation, the permits, and once the charger goes live, we track the power that we’re using, reimburse the property owner and also share some of the revenue. And even with fairly low utilization, it’s anywhere from $800 to $1,000 a year that the property owner is receiving in passive income.

Charging for charging

Charged: Can you tell me how the revenue breaks down?

Nathan King: Probably about half the revenue will go back to the utility. The price for drivers depends on the city. For example, in Boston, the cost per kilowatt-hour is quite high, so that’ll be reflected in the price we’re expecting drivers to pay. In the Midwest and Detroit, the cost per kWh is much lower. When we think about our pricing model, we set a couple of benchmarks for ourselves. We always want to have a per-kilowatt-hour price that’s competitive compared to DC fast charging, and a cost per mile below the price of gas.

The cost to install a Level 2 charger on a curbside is orders of magnitude less than installing a DC fast charger, so we don’t have that same capital investment that the DC fast charging companies have. Power is also less expensive because we’re not faced with demand charges.

Charged: Give me a quick history of the company.

Nathan King: We’re about three years old. My background is in what we call technical architecture—figuring out how to work with contractors, how to get permits from the city, how to get power connected to your buildings—which I enjoyed in some weird way. The city of New York was actually my client on two different projects.

During the pandemic, my family decided we needed a car. We live in Brooklyn, and we don’t have a driveway, so our car would be parked on the street, but there was nowhere for me to conveniently charge it.

That was true three years ago. It’s still true today. The closest place for me to charge was a private parking garage a mile away, and I would’ve had to pay for the parking, and the charging on top of that. It’s very expensive. So, we bought a gas car. And throughout 2020 I was thinking about this as a problem. There’s about 40 million vehicles in the US that park on city streets. If we are going to make this EV transition happen, how are we going to deal with this part of the market?

The aha moment was looking out my window and thinking, Why couldn’t I just toss a cord out, connect it to my building and plug my car in? Then I thought, what if I could make money from other drivers paying me for charging? The thing that I had going for me was all this experience in permitting things with cities, dealing with contractors, and three years later, here I am.

Charged: How many charging sites do you have up and running at the moment?

Nathan King: We have three in Brooklyn and four in Detroit. We are looking to install another up to 200 chargers in seven cities over the next 12 months. Our recent fundraising is supporting that activity. We have a couple of other smaller cities that we are looking to deploy in, but in terms of major metropolitan areas, it’s Boston, Alexandria, Detroit, Jersey City and Los Angeles. We’re also looking at a pilot opportunity in San Francisco.

Charged: It sounds like you’re on the verge of moving from the pilot stage into the scale-up phase.

Nathan King: Yeah. Earlier this year we announced that we had secured UL certifications for the charger. That’s a very important step in providing public charging. And between the RFPs that we’ve won and the grant money that we’re getting, our investment is really allowing us to build up our team and start to get these chargers in the ground.

The obligatory question

Charged: One more question, which I ask everybody. Why is the reliability of public chargers so abysmal?

Nathan King: Yeah, how do I not give you a 25-minute dissertation on this? I can call out design, but I think I’ve already talked about that enough, so I’ll call out the business model. Public Level 2 charging in the US is mostly a model in which property owners buy chargers from charger manufacturers and operate them themselves. But I think the right model for Level 2 charging is for the company that makes the charger to be the company that owns and operates it.

You’re then incentivized to design a charger that’s built to last, because your revenue is not based on making the sale. It’s based on earning continuous revenue—and that revenue goes down as soon as that charger stops working. Cities and utilities are experimenting with curbside charging, but ultimately they don’t want to be managing networks of thousands of EV chargers. It’s not what they do. Somehow we need to create accountability for the company that builds the charger to make sure that that charger stays up and running.

This article first appeared in Issue 69: July-September 2024 – Subscribe now.